Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

19 November 2024, 12:09

By Lakareber Kasline Gladys

In the rolling green hills of Pader district, where agriculture is not just a livelihood but a way of life, a quiet revolution is taking shape. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peasants and Other People Working in Rural Areas (UNDROP) has emerged as a beacon of hope, advocating for small-scale farmers’ rights to land, seeds, water, and biodiversity. For Uganda, a nation heavily reliant on agriculture, this initiative offers not just a roadmap but a lifeline to sustainable development.

According to the World Bank, agriculture is the backbone of Uganda’s economy, contributing approximately 25% of the national GDP and employing over 70% of the population. Despite its significance, small-scale farmers like Bosco Olum in Latanya sub-county grapple with the disconnect between global agricultural initiatives and harsh local realities. “I’ve attended more than five training sessions on promoting agriculture, but we’ve never received actual support to regulate market prices after harvest,” Olum laments, his hands calloused from years of tilling the soil. For him and many others, the open market economy undervalues their hard work, leaving their harvests devalued and their futures uncertain.

Nevertheless, Olum credits initiatives like the Project for Restoration of Livelihoods in the Northern Region (PRELNOR) for imparting lasting knowledge. The seven-year programme, which concluded in 2022, equipped farmers with techniques to improve income and food security. “The knowledge I gained continues to guide me,” he says with a faint smile, a testament to the enduring impact of well-implemented projects. Serving approximately 300,000 farmers, PRELNOR helped transform subsistence farming into more diversified and resilient agricultural practices.

For Irene Akello of Awere sub-county, the story is bittersweet. Benefiting from the National Agricultural Advisory Services (NAADS) in 2013, she received cassava seeds that temporarily boosted her yields. However, the programme’s short-term nature left many farmers, including Akello, yearning for more. “Some beneficiaries didn’t even use the chance they were given,” she recalls, disappointment evident in her voice. Established in 2001, NAADS aimed to empower rural farmers, yet its legacy remains a patchwork of successes and missed opportunities. During its first decade, the programme supported over 10 million farmers nationwide with agricultural inputs.

Bosco Odong, an agronomist at the Northern Uganda Farmers’ Centre in Pader, highlights the broader challenges. “The government often launches good projects but fails in execution due to poor supervision,” he explains. With over two decades of experience, Odong believes in UNDROP’s transformative potential. His organisation works tirelessly to bridge the gap, ensuring farmers have access to agro-inputs and technical support, particularly as climate change and land degradation increasingly threaten agricultural yields. According to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), small-scale farmers in Uganda, like those in Pader, produce over 70% of the nation’s food but receive only about 10% of government agricultural support.

Systemic challenges

Pader district Agricultural Officer Seydou Opoka Adolatona echoes Odong’s concerns, painting a stark picture of systemic hurdles impeding the realisation of UNDROP’s goals. “Out of 23 sub-counties, we have only 12 extension workers to oversee 97 parishes. Limited transport compounds the issue, leaving rural farmers underserved,” he explains. The shortage of extension workers and logistical challenges in rural Uganda undermine efforts to implement government agricultural programmes effectively, including those aligned with UNDROP. For instance, the Agricultural Sector Development Strategy and Investment Plan (DSIP), which seeks to modernise agriculture, has yet to reach many of Uganda’s most remote farming communities.

Despite these challenges, Opoka remains optimistic. He notes that programmes aligned with UNDROP, such as NAADS, played a pivotal role in transitioning farmers from post-conflict camp life to sustainable agricultural practices. The district is actively seeking partnerships to enhance resources, train farmers, and link them to better markets, all of which are essential for improving incomes and food security.

A global vision, local realities

At its core, UNDROP recognises that small-scale farmers, who produce much of the world’s food, bear the brunt of land dispossession, environmental degradation, and market instability. By advocating for their rights, the initiative not only protects livelihoods but also promotes agroecological practices that enhance biodiversity and climate resilience.

The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) notes that smallholder farmers in Uganda, particularly in Pader, face increasing threats of land grabbing, with over 70% of rural communities losing significant portions of farmland to large-scale commercial farming projects.

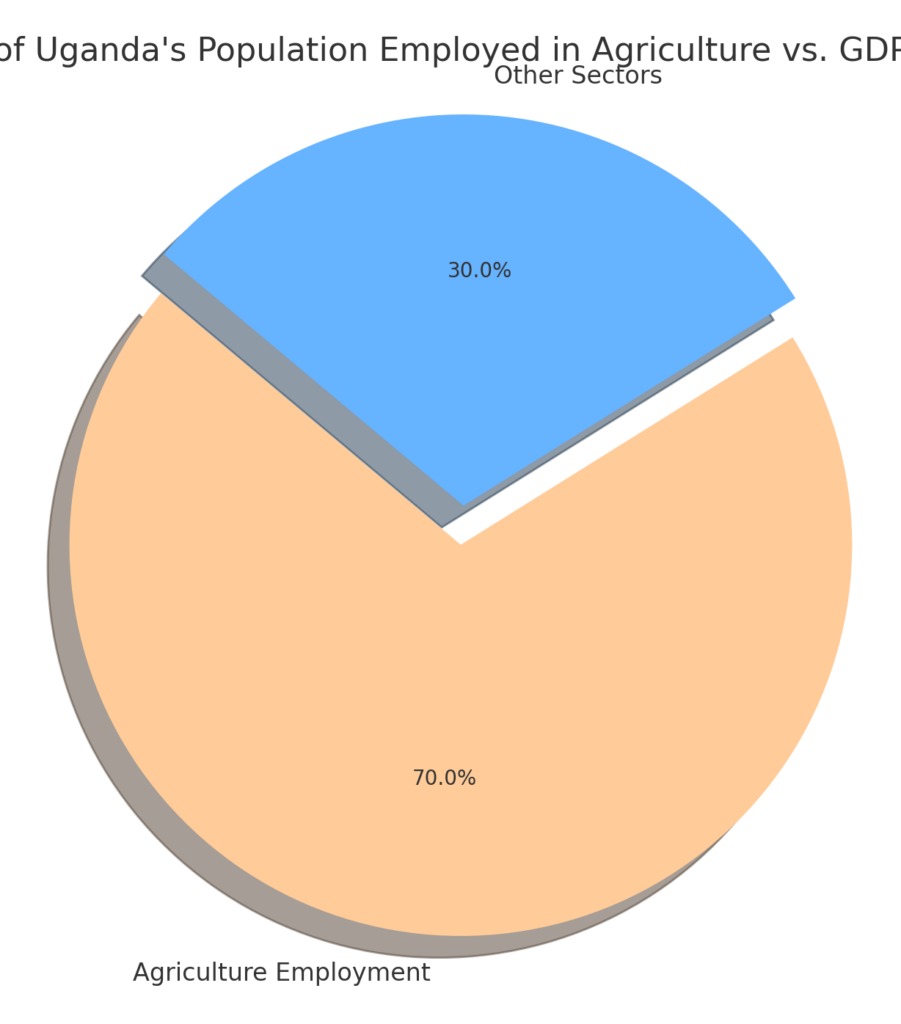

Graph 1: Uganda’s agricultural employment vs. GDP

The graph below illustrates the significant role of agriculture in Uganda’s economy. With over 70% of the population engaged in agriculture, the sector contributes approximately 24% of GDP. This underscores the urgent need for strengthened policies to support small-scale farmers sustainably.

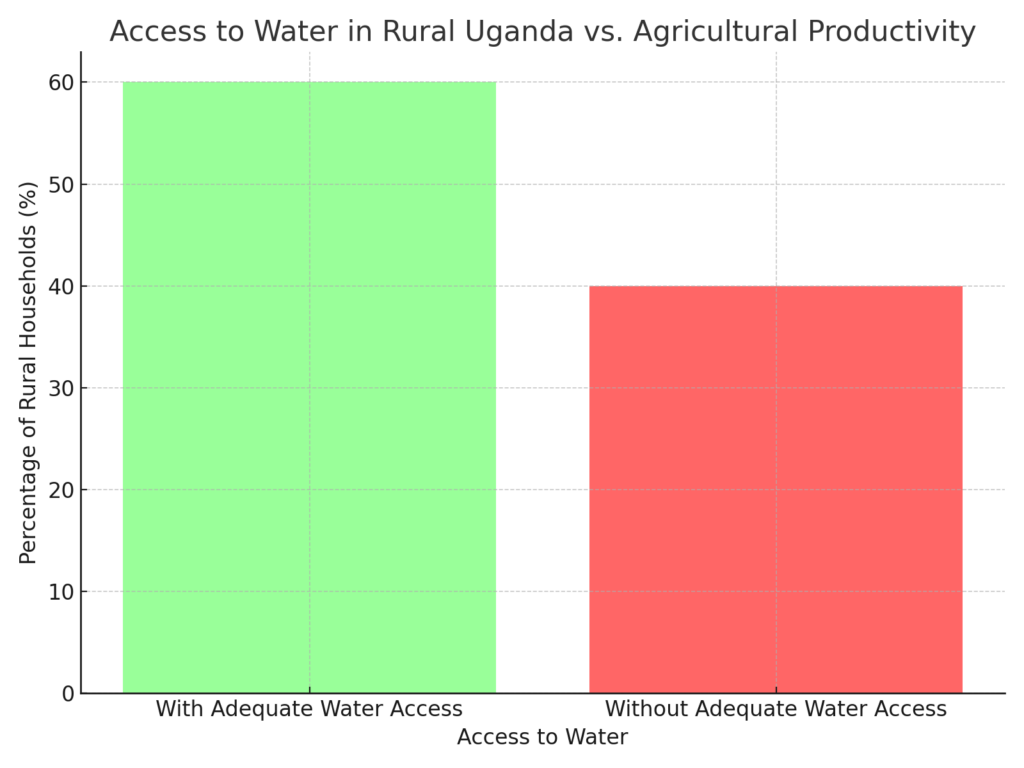

In Uganda, where water scarcity is an increasingly urgent issue, equitable access to water resources is vital. For farmers like Akello, irrigation systems could mean the difference between subsistence farming and achieving surplus yields. UNDROP’s advocacy for fair water management policies has the potential to transform lives, enabling even the most remote communities to cultivate crops year-round.

The Water and Sanitation Sector Performance Report reveals that less than 60% of rural households have access to adequate water sources, exacerbating challenges for agriculture.

Graph 2: Water access vs agricultural productivity in Uganda

The graph below illustrates the direct correlation between water access and agricultural productivity in Uganda. As irrigation systems and consistent water availability become more widespread, farmers achieve higher yields and improved food security.

However, the road ahead is fraught with challenges. While the open market economy fosters competition, it often leaves small-scale farmers vulnerable to exploitation. Bosco Olum’s call for price regulation resonates across rural Uganda, where volatile markets undermine productivity. Meanwhile, the rising cost of agricultural inputs such as seeds and fertilisers further squeezes the margins of smallholder farmers.

Hope amid challenges

Despite these obstacles, the farmers of Pader demonstrate remarkable resilience. Akello, Olum, and countless others embody the spirit of UNDROP—an unwavering commitment to their land and sustainable farming practices. Their stories highlight the urgent need for long-term investment—not only in knowledge but also in infrastructure, market access, and policy reform. According to the World Bank, Uganda’s agricultural sector could grow by 6-7% annually if systemic barriers, such as limited access to markets and inputs, are addressed.

As Opoka aptly observes, “Our farmers have the potential to feed the nation. All they need is the right support.”

The UNDROP initiative is more than a policy framework; it is a call to action. Governments must prioritise the rights of rural communities, ensuring that no farmer is left behind. Development partners also have a crucial role in funding projects that not only train farmers but equip them with the tools and resources to succeed.

In Pader, the seeds of hope are already sown. The district’s fertile lands, coupled with the determination of its farmers, provide an opportunity to turn UNDROP’s vision into reality. By addressing systemic challenges and fostering collaboration among stakeholders, Pader could become a model for sustainable agriculture in Uganda—and beyond. With the right support, smallholder farmers in Pader can contribute not only to Uganda’s food security but also to broader development goals, including poverty reduction, climate resilience, and economic empowerment.

The journey is long, but with every cassava root pulled from the earth, every seed saved and shared, and every harvest brought to market, Pader’s farmers move one step closer to a future where their rights are not only recognised but celebrated.