Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

15 October 2025, 22:09

By Lakomekec Kinyera

Under the scorching afternoon sun in a quiet neighbourhood of Pader Town Council, a 31-year-old man, who prefers to be called Okello, sits silently outside a friend’s shop. His face carries the weight of stories long buried in silence.

“I never thought I’d live to tell this,” he begins slowly, pulling up his trouser to reveal scars running across his calf. “She poured boiling water on me during a misunderstanding. It wasn’t the first time.”

Okello says his wife used to beat him whenever they disagreed. It began with insults, then slaps, and eventually escalated into serious physical violence. He reported the matter to his family, who involved his in-laws, but beyond family meetings, nothing was done.

“I went to the police, but they treated it like a joke,” he recalls. “As a man, they thought I should endure it.”

Eventually, Okello divorced his wife, fearing for his life. He now lives alone, occasionally seeing his one-year-old son.

“There are many men like me,” he says quietly. “But we don’t talk, because no one believes us.”

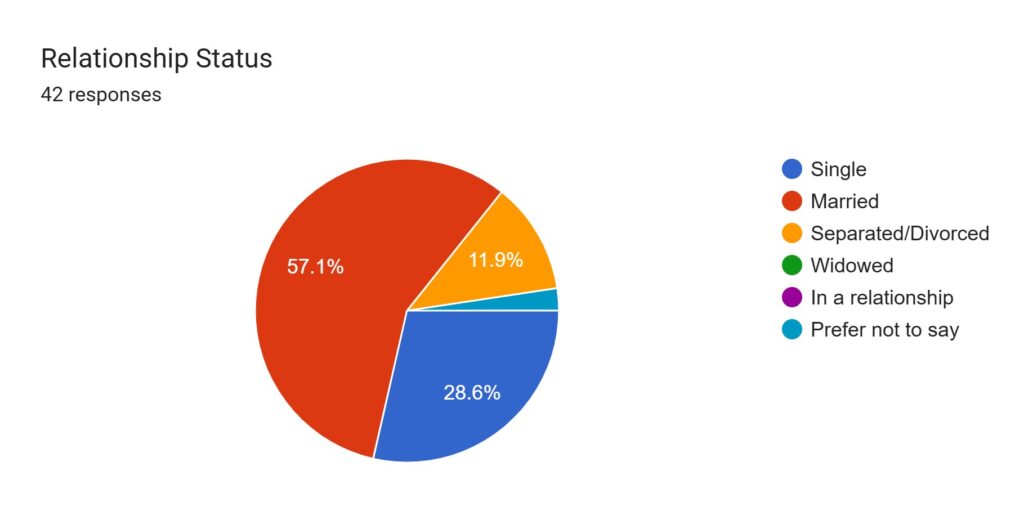

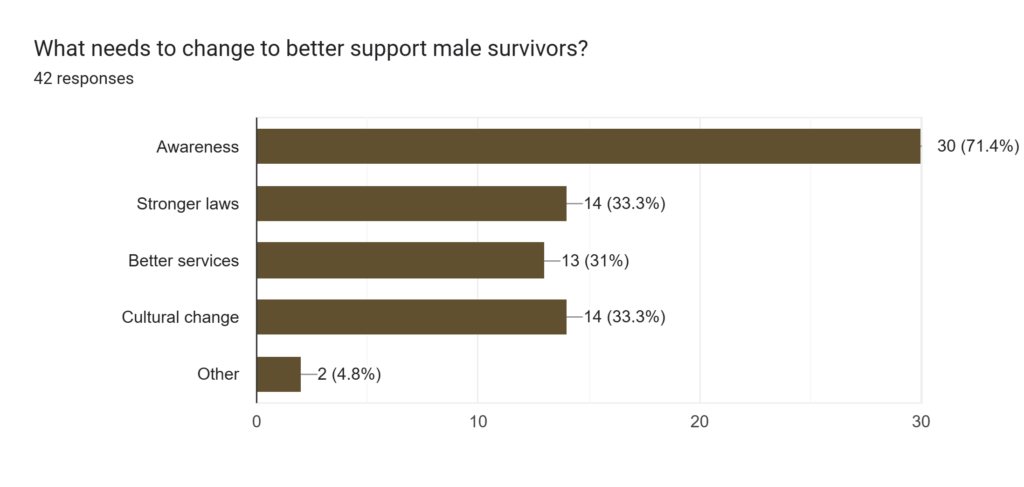

Okello’s story is just one of several findings from a survey involving 42 people in Pader and Agago districts. Eighty-five per cent were men living in semi-urban areas such as Pader and Lokole Town Councils.

Thirty-eight respondents reported emotional or verbal abuse, 24 experienced financial violence, 15 endured physical abuse, and nine were victims of sexual violence.

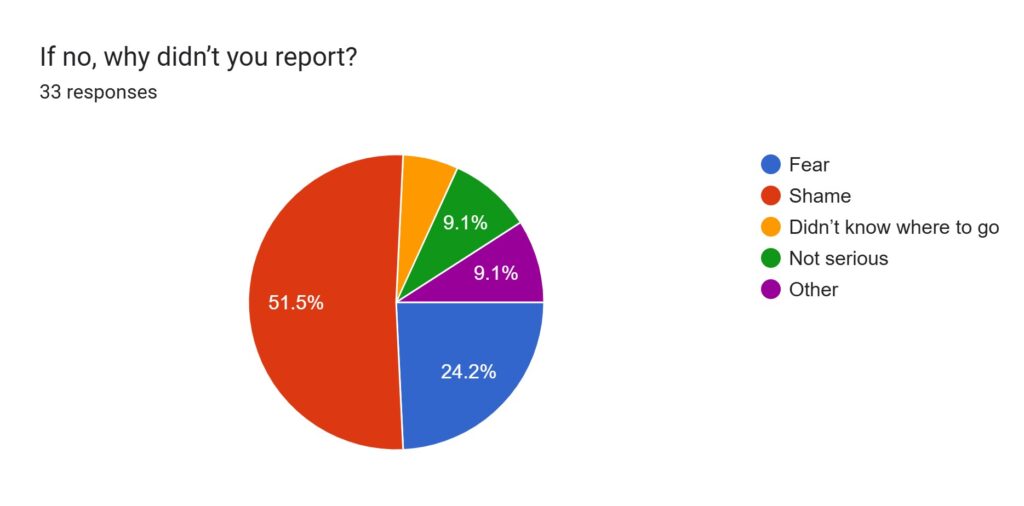

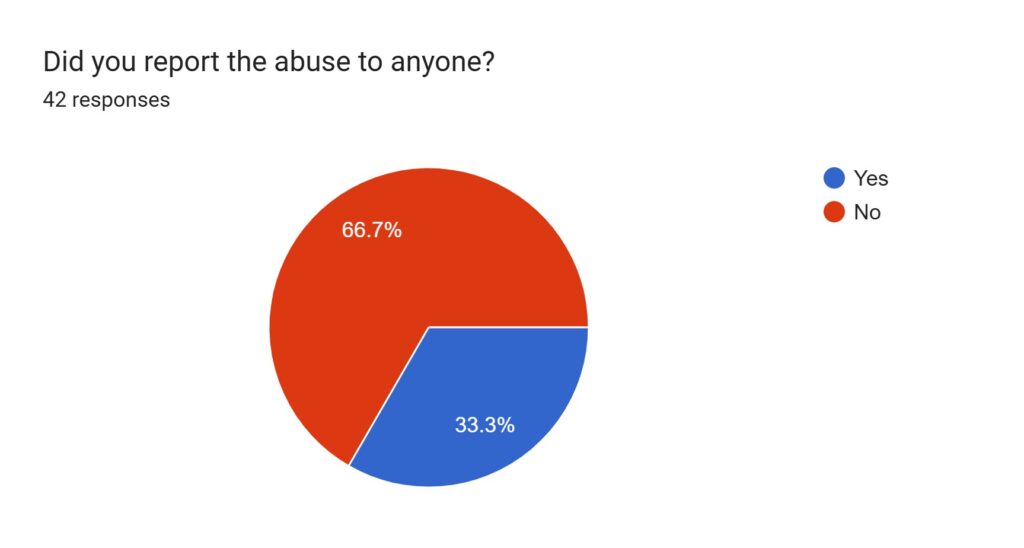

None of the male respondents had ever reported their abuse to formal authorities. Shame, stigma, and cultural expectations of masculinity were cited as the main reasons. Twenty-two men cited shame, eight feared repercussions, while others believed the violence was “not serious enough.”

Many turned to alcohol to cope. One man wrote:

“Men are desperate. Others drink 24/7 because they are always undermined when violence escalates.” Another added, “Men are going through a lot of abuse, but we feel left out.”

Brilliant Tito Okello, the Chairperson of Pajule Town Council, has confirmed witnessing the consequences firsthand.

“Male GBV is silent but deadly,” he says. “During Independence Day, we rescued a man who allegedly tried to commit suicide over domestic violence. He had been enduring abuse for years, as reported.”

He notes that most GBV reports involve women. Male cases are rare, not because they don’t exist, but because men remain silent.

“They fear shame. They fear being laughed at,” he adds.

His office relies on NGOs, probation officers, the police, and community dialogues to handle cases, but the reporting gap remains huge.

Cultural stereotypes portray men as strong and invulnerable. In many communities, it is unthinkable that a man can be a victim of violence from a woman. This stigma doesn’t just silence men—it breaks them.

Phillip Okot, the Prime Minister of the Pa Luo clan in Pajule, has mediated family disputes for years. He says male GBV often ends tragically.

“Some of these men die in silence,” he explains. “They’re abandoned by families, especially when conflicts involve property or polygamous unions.”

Polygamy and asset-related conflicts are major triggers of violence against men. In some families, men are denied access to property by their wives or even children.

“We’ve had elderly men found dead alone because they were neglected,” Okot reveals. “We encourage both men and women to speak out. Cultural institutions can help, but society must first accept that men can be victims too,” he adds.

Gender-based violence (GBV) in Uganda remains a deeply entrenched social and public health challenge, affecting both women and men. According to the Uganda Demographic and Health Survey, 39% of men aged 15–49 have experienced physical violence since the age of 15, compared to 44% of women. In the past 12 months, 14% of men reported experiencing physical violence.

Although women remain more affected, these figures reveal a significant but often neglected population of male survivors. Within intimate relationships, 34% of men have experienced physical, sexual, or emotional spousal violence. While 32% of female survivors sought help, fewer than 32% of male survivors did so. Cultural stigma and a lack of tailored services are key barriers to reporting.

Vicky Norah Odong, a gender activist, argues that Uganda’s legal frameworks and referral pathways often exclude men.

“When you read most legal instruments, men are referred to as perpetrators and women as survivors,” she explains. “This language creates bias and overlooks male victims.”

She notes that when men report GBV, their cases are often not taken seriously, particularly by law enforcement.

“Police treat it as a family issue. Economic violence against men may be acknowledged, but sexual violence is rarely recognised,” she says.

Odong calls for gender mainstreaming:

“Gender does not mean women alone. True equality must recognise vulnerabilities on both sides,” she adds.

Janet Lapat, a social worker in Pader District with LM International, says GBV against men often stems from financial disagreements, especially when the man is unemployed and the woman is the primary breadwinner.

“Unemployment and polygamy contribute greatly to tensions,” she explains.

She adds that alcoholism exacerbates these conflicts. In some cases, sexual performance issues also contribute to violence. Lapat emphasises the need for families to resolve disputes through dialogue, urging men to report such incidents to authorities or trusted friends in order to receive support.

Norbert Okii, Pader District Probation Officer, confirms the reporting gap.

“Between January and October 2025, we received zero formal cases from men,” he says. “Yet when women report cases, investigations often reveal that the man is the real victim.”

Because men are often arrested when women report incidents first, many choose to remain silent.

“The system is not designed to recognise men as survivors,” Okii says.

He believes male GBV should be treated with the same seriousness as female GBV.

Despite limited budgets, Okii reveals that his office collaborates with NGOs, community development officers (CDOs), and radio programmes to raise awareness. He notes that GBV against men is particularly common among literate, urban populations, especially those working in NGOs or formal employment.

“Most of these cases end in silent suffering or divorce,” he says.

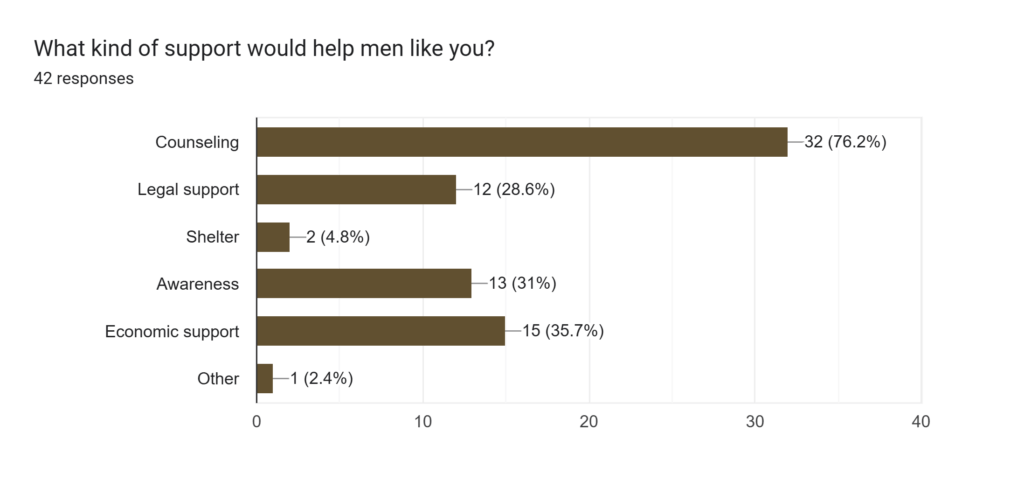

In the survey, most men said they needed counselling (35) and awareness campaigns (23) as priority interventions, with legal support and economic empowerment following closely.

One respondent wrote, “More sensitisation on GBV should be carried out. Men should not die in silence.”

Odong believes civil society has a critical role to play.

“When gender was first introduced in Uganda, it was misinterpreted to mean women only. Advocacy must now focus on gender inclusiveness,” she explains.

She also urges religious, cultural, and local leaders to work together.

Experts agree that ending GBV requires a shift in cultural narratives. Men should not be expected to “man up” through pain. They need safe spaces, supportive legal systems, and recognition of their suffering.

Okot, from the Pa Luo clan, believes cultural institutions can help:

“We can dialogue with perpetrators and protect victims, regardless of gender,” he says.

Okello, the survivor, says he is not seeking revenge but only justice and recognition:

“I want people to know men can be hurt too,” he says softly. “We need help before more lives are lost.”

Gender-based violence is not only “women’s issue.” It is a human issue, rooted in cultural, legal, and social systems that often fail to protect men. Behind every unreported case is a father, a brother, a son enduring silent suffering. Recognising male survivors does not undermine women’s rights—it strengthens the fight against violence for everyone.