Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

Rapa FM Pader

31 October 2025, 19:46

By Lakomekec Kinyera

“The Click That Kills: Uganda Faces a Growing Online Wildlife Threat Before Any Formal Case Is Recorded“

In Uganda, the forest is no longer the only hunting ground. Wildlife traffickers have moved online, exploiting social media and messaging apps to buy and sell endangered species. With every click, scroll, and private chat, animals like pangolins, elephants, and rhinos vanish into a hidden trade, taking advantage of legal gaps before a single formal case is recorded.

From Forest Trails to Digital Channels

Wildlife crime has expanded far beyond forests and hidden paths. Smartphones, social media, and encrypted messaging apps have created a new frontier for poachers. For communities near national parks, the threat is often invisible until law enforcement intervenes.

A reformed poacher from Pader district, who preferred to be called Opiro, explained: “Poachers today often prefer to engage in illegal wildlife products online. It is cheaper than physical meetings. A buyer in an area can coordinate from hundreds of kilometers away. People in villages don’t know what happens after the animal is taken.”

Hangi Bashir, spokesperson for Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), observed: “The Internet is wide and extensive. You can’t even tell. Where we have the Internet, we know there’s a dark Internet which we don’t access. So who knows what’s happening there? Actually, it is difficult now. And almost everyone is a journalist, so it’s tricky.” He added that economic pressures drive people into illegal activities, while syndicates exploit both technology and poverty.

Hangi confirmed that currently, the UWA does not have control over how people use their handles in respect to wildlife exposure to danger of online traffickers.

The stakes are high. TRAFFIC’s 2018 Uganda Wildlife Trafficking Assessment estimates that more than half of the world’s remaining mountain gorillas, 50% of Africa’s bird species, nearly 40% of Africa’s mammals, and 19% of amphibians in Uganda are at risk from illegal trade.

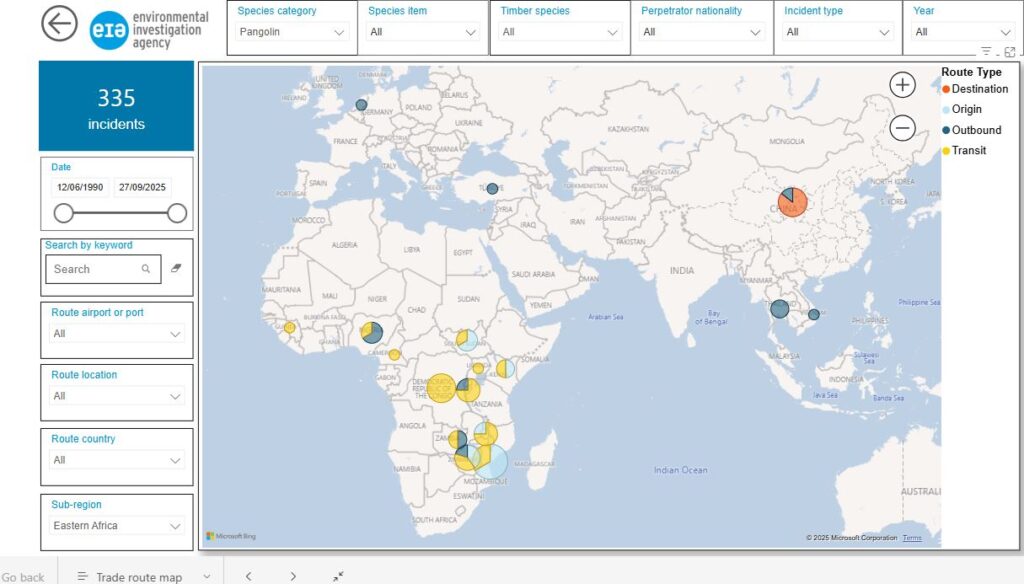

Uganda’s Role as a Transit Hub

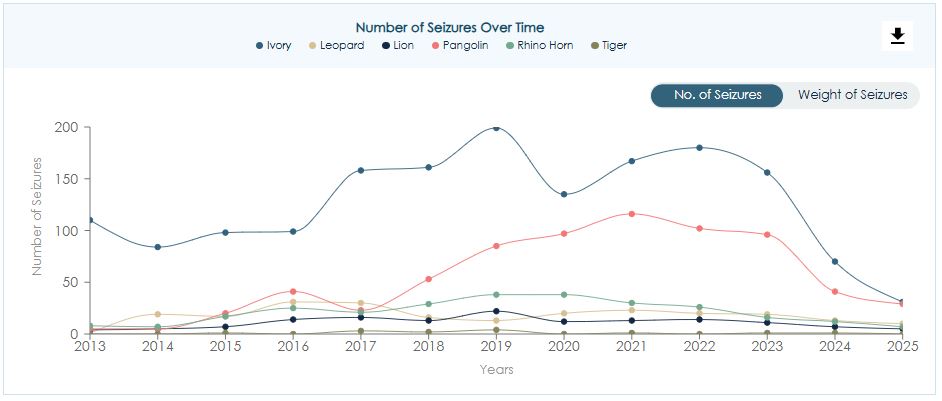

Uganda has long served as a transit point in Central and East Africa. Ivory, rhino horn, pangolin scales, and bushmeat traverse national borders. TRAFFIC’s 2018 report identifies key routes: South Sudan to Kitgum, DRC to Kampala, and Uganda to Istanbul, Turkey. Criminal networks leverage weak border checks, corruption, and complex logistics to transport illicit wildlife.

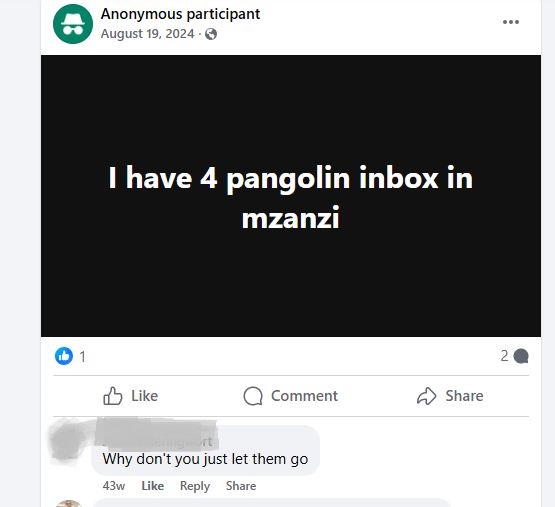

Pangolins, nocturnal and elusive are particularly vulnerable. African pangolins increasingly supply Asian markets, where scales are used in traditional medicine and meat is consumed as a tonic. Surveys in Chinese and Vietnamese cities show 60–68% of buyers intend to repurchase, with about half influenced by sellers.

Lauben Isingwire, executive director of Wildlife Conservation and Community Initiative (WICCODI) around Queen Elizabeth and Bwindi national parks, explained: “Traffickers now employ phones for coordination, not hunting. They know the animal’s habits and routes. A single transaction can involve multiple actors, from the poacher in a forest to a buyer abroad.”

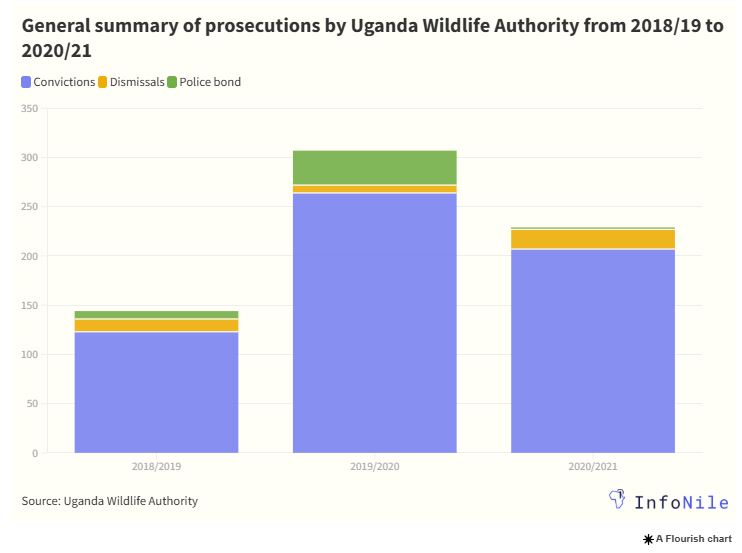

Between 2017 and 2021, Uganda recorded 842 wildlife crime cases, resulting in 744 arrests. Of these, 579 suspects were prosecuted, but only 313 were convicted, a 37% conviction rate. Monetary losses are estimated at USD 8.46 million, with USD 8.02 million recovered through seizures, mainly elephant ivory, rhino horn, and pangolin scales.

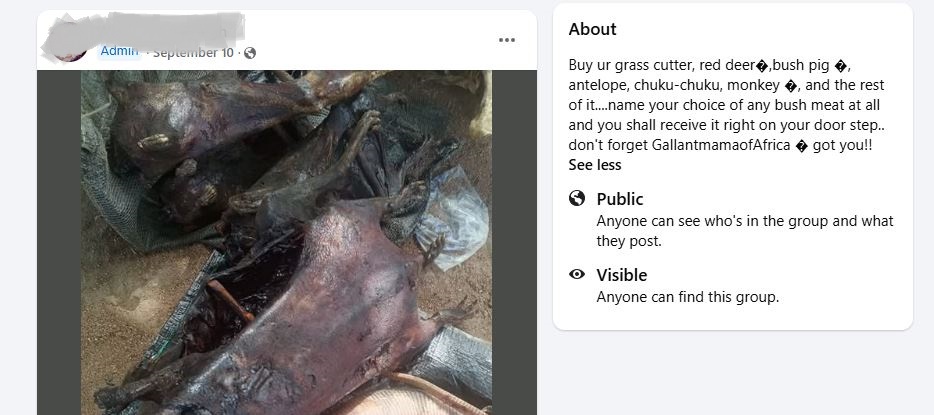

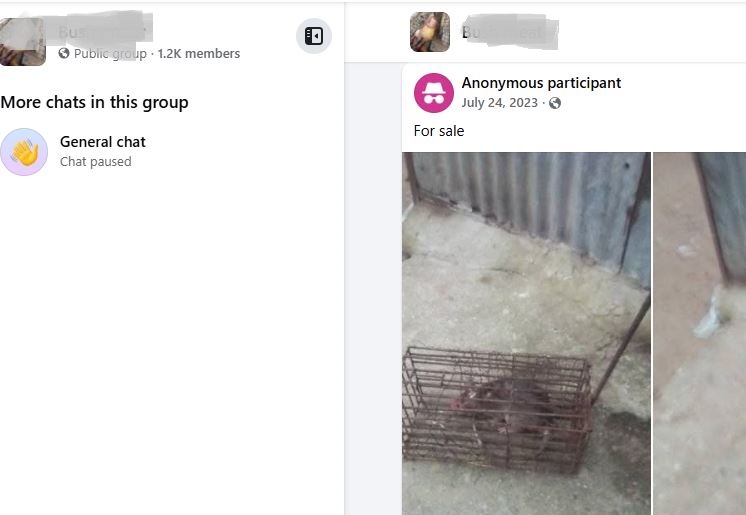

Modus Operandi: From Forest to Facebook

Wildlife traffickers in Uganda have adapted to evolving enforcement measures, combining traditional hunting methods with digital networks to reach buyers. Historically, poachers relied on local knowledge, traps, and physical networks to capture animals such as pangolins, elephants, and bushmeat species. Today, traffickers increasingly coordinate hunts, advertise products, and arrange payments via mobile phones, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook, minimizing face-to-face interactions.

Online platforms allow traffickers to conceal identities and evade law enforcement, creating a new layer of complexity. Larger shipments, like ivory or rhino horn, require cross-border coordination, bribery, clandestine storage, and smuggling by air or sea. Smaller shipments, including bushmeat or pangolin scales, are easier to manage and increasingly facilitated through digital marketplaces.

Local conservationists note that phones and coded communication link reformed poachers to buyers, even if online evidence remains difficult to trace.

Isingwire of WICCODI stated: “Well, I haven’t seen one. The only thing that I know, of course, people are using phones for connections in terms of wildlife trafficking. Not necessarily only social media like Facebook or WhatsApp, but people are employing those devices to conduct transactions.”

Opiro, a reformed poacher in Pader district, said he had encountered posts exposing wildlife to trafficking, including monkeys and wild dogs, targeted for meat, money, or cultural purposes. “Among the posts I came across include monkeys killed and eaten by people, wild dogs, among others.”

He suspected such activities occurred in neighboring Kenya and parts of Uganda, including Karamoja, where hunting is part of daily life. “Because of the exposure of the pictures of wildlife online, especially on social media including WhatsApp groups, Facebook, and others, the animals become vulnerable to trafficking.”

Experts emphasize that understanding traffickers’ methods from the bush to online platforms is critical. By combining field intelligence, cyber monitoring, and community-based reporting, authorities can disrupt networks, protect endangered species, and prevent the digital expansion of illegal wildlife trade.

From Taboo to Protection: How Culture Saves Species

In Uganda, culture remains an underappreciated ally in wildlife conservation. Chief Kassimiro Ongom of Patongo, Agago District, explained that traditional practices often shield species from exploitation.

“There are ways how the culture conserves wildlife through proclamations known as ‘mwoc,’ where certain animals are declared sacred and cannot be eaten. For example, wolves, locally called ‘Orudi,’ are protected by specific clans.” He added that ceremonial uses of wildlife products, such as leopard hides for clan chief’s burials or ostrich eggs for newborns, are strictly regulated and conducted with UWA permission.

Uganda’s Wildlife Act, 2019, explicitly acknowledges cultural institutions in conservation, urging collaboration with UWA to regulate traditional practices. Integrating culture into modern conservation strategies makes communities active guardians, curbing both physical poaching and emerging online threats.

Ongom revealed the role of cultural institutions in wildlife protection. “In the past, cultural institutions contributed to wildlife destruction. Today, with laws in place, we sensitize locals against poaching,” he said. Traditional practices, like using leopard skins for clan burials, “lwit” (hyena noses) for security, or “canga” (ostrich eggshells) for newborns, are ceremonial and permitted by UWA.

Opiro added: “Some poachers are local people who connect to foreigners to hunt animals. But culture, if respected, discourages such acts because people understand the importance of wildlife and the laws protecting them.”

Species Under Siege

Uganda and the wider East African region host some of Africa’s most iconic species, many under unprecedented pressure. TRAFFIC’s 2018 Uganda Wildlife Trafficking Assessment ranks pangolins as the most trafficked mammal globally, with Uganda a key source of both meat and scales. Between 2017 and 2021, Uganda reported 842 wildlife crime cases, with pangolins, elephants, rhinos, and tortoises among the most frequently targeted.

Annually, about 15,000 elephants are killed for ivory, and over 600 kilograms of pangolin scales were seized in a single 2023 operation. Birds, such as the grey crowned crane, are heavily trafficked, mainly to Asia. Isingwire observed: “Online trafficking is fueled mostly by local people who know animal behavior, but some are connecting through phones or social media to reach buyers beyond our borders.”

Across East Africa, similar trends persist: Tanzania and Kenya report poaching of elephants and rhinos, while pangolins increasingly supply China and Vietnam. Local hunting traditions, high international demand, and online networks intensify threats. Without strong enforcement and community engagement, these species face continued decline.

Legal Framework and Inter-Agency Action

Uganda’s Wildlife Act, 2019, strengthens wildlife protection, imposing penalties up to shillings 20 billion, life imprisonment, or both. The Act institutionalizes community involvement through revenue-sharing and Wildlife Committees, empowering UWA to supervise protected and community wildlife areas.

Enforcement is bolstered through the Joint Wildlife Coordination Taskforce, comprising UWA, Uganda Police, customs, and the Financial Intelligence Authority. The taskforce has increased arrests, seizures, and prosecutions while improving intelligence sharing. Earlier this year, Police and the Uganda Wildlife Authority Crime Unit (UWACU) arrested two suspects in Pader District for allegedly attempting to sell a pangolin at a local lodge.

Aswa East Regional Police Spokesperson Joe Oloya confirmed that joint operation, noting that while police assisted in the arrest, wildlife-related crimes are handled by UWA’s specialized crime unit.

A landmark case, Ochiba Pascal vs. Uganda (2022), resulted in life imprisonment for possession of 9.55 kg of elephant ivory without a valid permit. The Chief Magistrate emphasized that weak enforcement threatens species survival.

Corruption remains a challenge. The Basel Institute on Governance notes political and economic elites’ involvement in ivory stock thefts. Meanwhile, the FIA in 2023 classified wildlife crime corruption as “medium risk.” Uganda remains both a source and transit country for exports to China, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Singapore. Between 2017–2021, 840 wildlife crime cases were reported, with a 37% conviction rate.

Technology as a Conservation Ally

Technology is transforming wildlife protection. In July 2024, UWA received six advanced drones from the UNDP to monitor remote terrain and detect illegal activity. What has Uganda done with it?

USAID’s Online Wildlife Offenders Database (OWODAT) has tracked over 3,400 cases involving nearly 6,000 suspects by early 2024. Platforms and the Coalition to End Wildlife Trafficking Online leverage AI and content moderation to remove illegal wildlife posts; by 2023, one social media giant deleted 7.6 million posts. UWA PRO Hangi also warned about the risk associated with exposing wildlife on social media.

Cybercrime analyst Wilkie Kidega noted: “Traffickers hide behind encrypted apps, emojis, and disappearing messages, but tracking IPs gives us the edge. By identifying the digital footprint, we can trace offenders and dismantle networks before animals are lost.”

He explained that social media providers know the keywords used, even on encrypted platforms. Kidega said UWA can track offenders more effectively with data miners and phone records, though online tracking is expensive and time-consuming.

Chief Ongom warned that traffickers increasingly use online platforms. “People use coded names and passwords, and wildlife products are sold in dark markets, making arrests difficult,” he said. Some game rangers are complicit, allowing hunting to continue around Kidepo National Park. In areas like Paimol and Adilang, locals kill about eight animals daily. Terms like ‘bel,’ meaning sorghum for roasted bushmeat disguise illegal activity.

Ongom urged UWA to involve cultural leaders, blending traditional authority with law enforcement to combat wildlife trafficking both offline and online.

The Human Element: Hope in Action

Wildlife trafficking is not only a conservation issue but also an economic and social one. Uganda loses an estimated shilling 1.8 billion annually in tourism revenue due to wildlife crime. A kilogram of pangolin scales fetches hundreds of dollars abroad, making poaching lucrative.

UWA PRO Bashir emphasized: “We provide education, revenue-sharing, and alternative livelihoods, but traffickers exploit poverty and lack of awareness.” To his side, Isingwire said: “Many youths see poaching as an opportunity because it is lucrative and low-risk when conducted online.”

He explained: “We rescue and rehabilitate pangolins, then release them back to the wild…we work with reformed poachers to improve their livelihood, so they forget about wildlife meat…phones are used in the trade, but our interventions focus on training, awareness, and sustainable alternatives like catfish and vegetable farming.”

Regional cases, like Kenya’s 2025 giant ant smuggling ring coordinated entirely online, show digital wildlife crime extends beyond iconic species. South Sudan continues largely traditional trade, but emerging digital networks indicate a regional shift is imminent.

Opiro stated that; “Even if online trafficking is invisible, every click contributes to species loss. Communities, government, and NGOs must act together before it’s too late.”

Uganda’s endangered species such as; pangolins, elephants, rhinos, and others face dual threats from human greed and digital innovation. Every intercepted message, every seized shipment, and every life saved counts. With wildlife trafficking moving online, how is Uganda preparing to tackle the emerging digital threat before it pushes more species to the brink?