Voice of Lango

Voice of Lango

Voice of Lango

Voice of Lango

4 October 2025, 4:22 pm

By Aceng Patricia Amne

When Olwol Road in Lira City was finally completed under the Uganda Support to Municipal Infrastructure Development (USMID) programme, it was expected to transform one of the busiest commercial corridors in the city.

Instead, questions now dominate public debate: did the 37.6 billion-shilling project deliver value for money? Who is accountable for its design flaws and delayed works? And what lessons does this case hold for Uganda’s broader urban infrastructure drive?

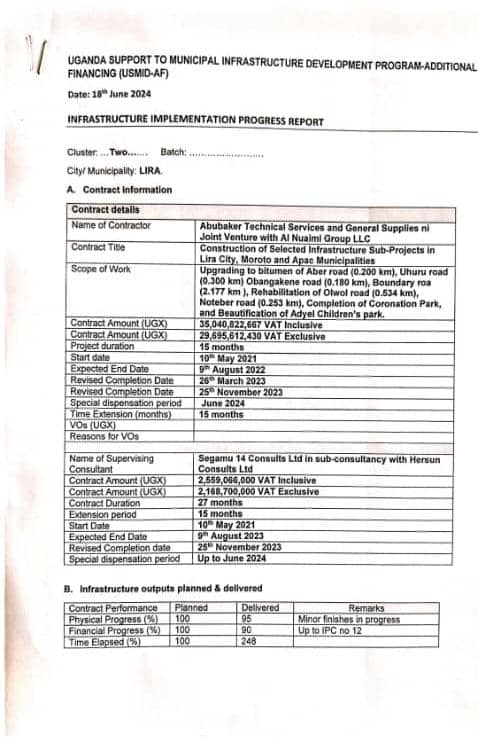

Olwol Road formed part of Phase II of the USMID programme, a World Bank–funded initiative designed as a Programme-for-Results (PforR) to improve infrastructure in Uganda’s municipalities.

In Lira, Phase 1 had already seen the rehabilitation of Obote Avenue, Soroti, Kwania, Maruzi, Aduku Road and Aroma Lane, as well as the beautification of the Lira Main Roundabout and Coronation Park—at a total cost of 11 billion shillings.

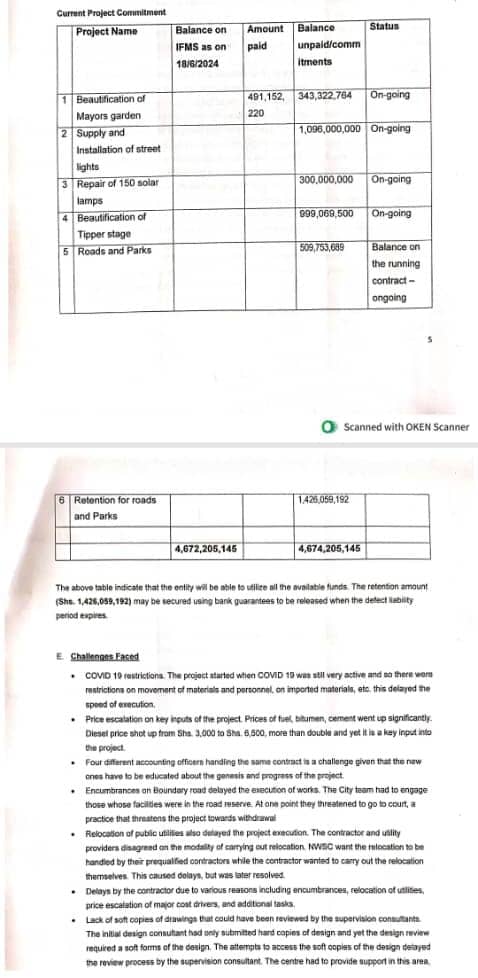

Phase II extended the works to other key roads, including Obangakene Road (0.18 km), Noteber Road (0.251 km), Aber Road (0.204 km), Olwol Road (0.534 km), Uhuru Road (0.3 km), and Boundary Road (2.177 km). It also included the construction of a children’s park. The contract for this phase was awarded to Abubakar Technical Services Limited, with a total package valued at 37.6 billion shillings.

For Olwol Road specifically, the original design included a 20-metre-wide carriageway, with street lighting, drainage systems, pedestrian walkways, and signage. With an allocated budget of 1 billion shillings, city leaders pledged that the project would improve mobility, ease business operations, and beautify Lira City’s western division.

Almost from the outset, however, the project encountered difficulties. Residents accused the city of encroaching on private land, dragging Lira City Council into court battles that slowed progress. Because compensation was not provided for affected property owners, engineers were forced to adjust the road alignment, compromising both the planned width and design features.

Etura Ambrose, Senior Physical Planner for Lira City, admitted mistakes had been made.

“We failed to reclaim space on the road reserve, and construction went ahead without reviewing the design. That was a mistake,” he said.

The consequences are now evident. The road lacks pedestrian walkways, street signage, speed bumps, and adequate drainage. During rainy seasons it floods easily, disrupting transport and creating safety hazards. Local carpenter Samuel Awio summed up the concerns:

“There’s no separation between vehicles and pedestrians, and no warning signs or lighting at night. It’s not safe.”

City officials have acknowledged shortcomings. Robert Okello Ayo, Lira City spokesperson, explained:

“There was an issue with the drainage plan. That’s why it wasn’t implemented properly.”

Even Mayor Sam Atul conceded that although the road had improved accessibility, it fell short of expectations.

“The project needs to be reviewed to address safety concerns. A road must not just be built, it must serve,” he said.

The combination of design flaws, flooding problems and missing features has fuelled scrutiny from citizens and governance experts alike.

Dr Morris Chris Ongom, former chairperson of the Lira City Development Forum (CDF), was one of the earliest critics.

“The project fell short of community expectations because of design flaws, contractual abuse, and governance failures,” he argued.

The CDF—which is mandated to guide urban policy through advocacy, engagement, and cooperation—had flagged issues early but, according to Ongom, was ignored.

“If compensation had been done, Olwol would today be much wider. Instead, the manholes were left exposed, metallic covers were stolen by street children, and public safety was compromised,” he said.

He also accused the contractor of overstretching the admeasured contract terms, leading to scope and budget variations.

“A project meant for 18 months dragged to nearly three years,” he noted.

The USMID Programme Operational Manual (2013, Section 5.2) requires municipal projects to follow procurement procedures, safeguard social and environmental rights, and ensure adequate community consultations.

Likewise, the Public Procurement and Disposal of Public Assets (PPDA) Act, 2003 places contract management responsibility on the procuring entity—in this case, Lira City Council. But Ongom insists oversight was inadequate.

“I raised issues, I even monitored the project with my own money. But accountability was bypassed. The Mayor struggled because the people around him didn’t understand project management.”

Compensation disputes also violated the Land Acquisition Act (1965), which obliges government to provide fair compensation when private property is acquired for public works. With no compensation offered, Olwol Road remained narrow, reducing its long-term value.

The National Urban Policy (2017) further stresses the importance of inclusive governance, noting that citizens should be involved in all stages of urban project planning, implementation, and monitoring. Yet residents say their voices were sidelined throughout.

Not all officials accept the criticisms. Omara Elem, Councillor for Lira City West A and Secretary for Finance and Administration, defended the design.

“I don’t agree with the notion that Olwol Road is narrow. People are only looking at the carriageway and not the utilities. You can’t have a wide carriageway and a small drainage. If water fails to flow properly, the road will collapse eventually.”

He argued that councillors approved the design with long-term resilience in mind, prioritising drainage and utility space over carriageway width. For him, accountability lies not in road size but in balancing infrastructure with sustainability.

Nevertheless, his defence raises further questions: were these priorities clearly explained to citizens? And were public consultations truly meaningful? For residents and business owners along Olwol Road, the gaps are not theoretical but practical.

Shops are regularly flooded during heavy rains, pedestrians face increased risks due to the absence of walkways, and poor lighting undermines safety at night. City official Sarah Awor Angweri admitted dissatisfaction.

“As City, we are not content with how this project was implemented. We tried pushing for completion, but let the engineer clarify the value for money.”

The debate over Olwol Road reflects wider concerns about Uganda’s urban infrastructure projects. With USMID investments spread across multiple municipalities, issues of design integrity, compensation, and citizen engagement are increasingly pressing.

Accountability, analysts argue, is not just about expenditure but about whether projects fulfil their intended purpose. Who ensures design quality? Who bears responsibility for compensation failures? Why were safety features neglected?

The PPDA Regulations (2003) require procuring entities to conduct supervision and report regularly on project progress, yet Olwol Road illustrates how citizen oversight can be sidelined. For Ongom, the lesson is stark:

“Citizens must get involved if they want standard work. At the moment, governance issues are confined to a few hands, leaving the majority without a say.”

Olwol Road was intended to symbolise modernisation in Lira City under USMID. Instead, it has become a case study in accountability gaps—where design compromises, weak governance, and limited consultation have left residents questioning whether the project delivered value for money.

As Uganda continues to expand its urban infrastructure, Olwol Road stands as a cautionary tale: a road may be built, but if it fails to serve, can it truly be called development?